In mid-July, the FCC voted to strip education from the Educational Broadband Service (EBS) spectrum band, the only slice of public airwaves dedicated to educational purposes. One of the major complaints from the educational community about the FCC’s rush to a partisan 3-2 vote was the lack of a conclusion in the T-Mobile/Sprint merger.

What does EBS have to do with the merger? Given that Sprint controls nearly 70% of all EBS licenses through lease agreements and also a significant portion of the commercial portion of the 2.5 GHz spectrum band – known as Broadband Radio Service – it seems logical that some conclusion in the merger proceeding should have occurred before any vote on changing the EBS rules. For instance, regulators may want to require New T-Mobile to divest some of this precious 2.5 GHz spectrum to a competitor in order to balance competition. However, the FCC moved forward in early July to radically change EBS before a merger decision.

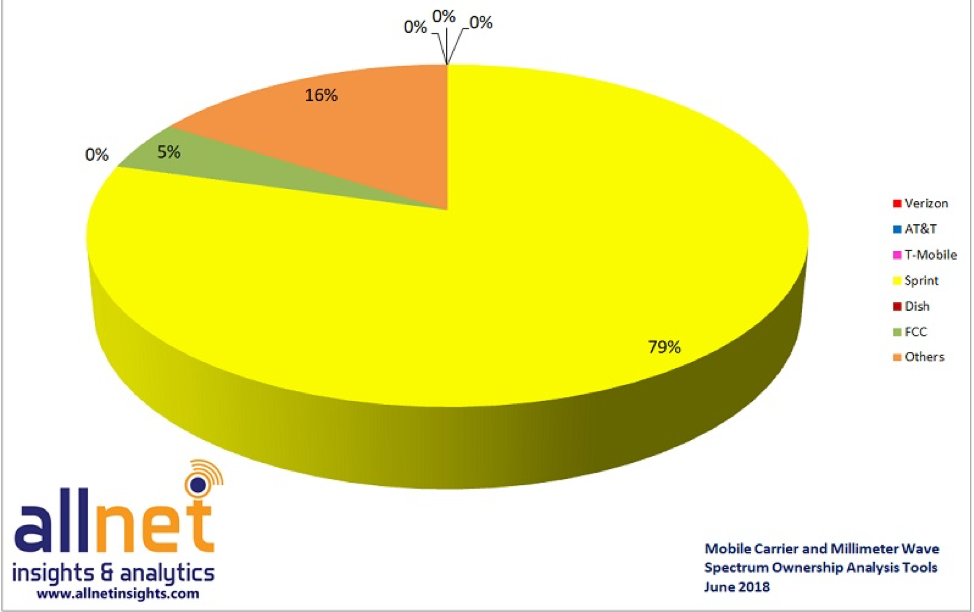

Why does it matter? In order for 5G deployment, wireless companies need the largest possible chunks of contiguous spectrum at low, medium and high frequencies. While there is adequate low- and high-band spectrum in use today, mid-band is in short supply. Sprint is the only major carrier with 160 MHz of mid-band spectrum (their EBS leases plus their BRS licenses) in the top 100 markets, giving them a significant advantage to build a superior 5G network quickly. Indeed, this treasure trove of spectrum is one of the primary reasons T-Mobile made an offer to acquire Sprint.

As of last Friday, the merging companies cleared another hurdle on their long journey to a final decision from state and federal regulators. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) approved the merger between Sprint and T-Mobile but only after requiring a variety of conditions to clear the way for another national wireless carrier to enter the market. That new entrant will be television provider DISH Network.

In addition to buildout requirements imposed by the FCC, the DOJ is requiring Sprint and T-Mobile to:

- Divest Boost/Virgin Mobile and its 9.3 million pre-paid customers to DISH for $1.4B.

- Allow DISH to use New T-Mobile network for seven years on a wholesale basis.

- Allow DISH the option to buy Sprint’s 800 MHz spectrum after three years for $3.6B.

- Allow DISH to the option to buy 400 stores that would be closed.

- Allow DISH to the option to buy 20,000 cell sites that would be decommissioned.

- Require New T-Mobile to implement electronic SIM cards in its phones, making it easier for consumers to switch providers.

All along, Sprint has complained to regulators about its inability to compete. As the fourth-largest wireless carrier in the nation with roughly 54 million customers, it has struggled in recent years to make investments and retain its customer base. But if Sprint cannot compete now, will the DOJ’s conditions be enough to fuel DISH as a true competitor?

For any company to survive in mobile business, key ingredients are needed, including existing cash flow, ability to raise additional capital, adequate spectrum assets, a customer base, and equipment in form of towers, base stations and phones. Many analysts remain skeptical that the conditions will provide DISH with enough key ingredients to bake their own 5G cake. In fact, their current assets are much worse off than keeping Sprint as a 4th competitor. DISH:

- Holds an inferior (perhaps limiting) portfolio of spectrum as compared to stand-alone Sprint.

- Operates a pay-tv business that has a declining customer base.

- Generates just $1B of free cash flow, when major national wireless companies are spending up $5 to $23B per year.

- Will have just 9.3 million pre-paid customers (from Boost), the least desirable kind in the mobile business, compared to Sprint’s 54 million as a stand-alone company.

- Faces a difficult road ahead to develop new handsets and tower equipment compatible with its spectrum holdings.

Investors and analysts are not oblivious to these facts. In fact, recent analyst notes project DISH could lose 10% of its market value while also facing a downgrade of its debt rating from Moody’s. The same analysts project New T-Mobile to gain up to 20% in market value. One reason for optimism is that T-Mobile will be the only wireless carrier with a huge chunk of contiguous mid-band spectrum – the 2.5 GHz band – for at least two to three years.

Voqal has asked regulators to require divestiture of Sprint’s 2.5 GHz assets in order to fuel a second competitor with adequate mid-band spectrum. In addition, Voqal President John Schwartz recently wrote an opinion piece for Law360 that lays out a strong case for why divestiture of EBS should be a requirement of any merger agreement between T-Mobile and Sprint. Tragically, the DOJ is convinced the mishmash of DISH spectrum combined with just 14 MHz of Sprint’s low-band spectrum – an asset New T-Mobile is happy to shed – will be enough to build a nationwide wireless network.

The FCC and DOJ seem awfully interested in winning the “Race to 5G” but it’s difficult to see why divestiture of 2.5 GHz spectrum would be a worse option than Friday’s announced deal. Offering two carriers roughly 100 MHz of prime mid-band spectrum would fuel two companies to offer 5G service quickly. It may be years before AT&T and Verizon can get access to similar mid-band assets, which all carriers claim is a crucial component of a robust 5G network. T-Mobile CEO John Legere confirmed this observation on the day the deal was announced.

The final remaining hurdle for the merger will be decided by the court. Attorneys General from 13 states and the District of Columbia have filed a federal lawsuit to block the deal on the grounds that it is anti-competitive. A court date has been set for early October.

As a strong believer in ensuring that the United States’ airwaves should be leveraged to the greatest public benefit, Voqal will continue to engage on this issue. Stay tuned for further updates.