In his latest article, Voqal’s Mark Colwell examines how the success of the recent Rural Tribal Priority Window is evidence that the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) should open a Rural Education Window for Educational Broadband Service licenses.

Last week, the FCC’s first-ever Rural Tribal Priority Window (TPW) came to a close. This special spectrum application window allowed for rural tribal nations to apply for valuable Educational Broadband Service (EBS) frequencies over their lands that had never been licensed. EBS is spectrum in the 2.5 GHz range that is useful for wireless broadband buildout due to its ideal blend of coverage and capacity.

The FCC received applications for spectrum on 266 separate tribal lands during the TPW. In all, 418 applications and amendments were filed with the Commission. The TPW, which was originally set to run from February 3 to August 3, was extended for an additional 30 days by the FCC in late July. Many public interest groups had advocated for a longer extension to allow tribes battling COVID-19 more time to apply. The extension resulted in 107 new applications being filed, which is significant. According to a press release, FCC staff will review filed applications starting immediately requesting additional information if needed, then seek public comment on the applications before processing them.

The release also explains that “any remaining unassigned 2.5 GHz spectrum will be made available by auction,” which is expected to happen in the first half of 2021. The decision to auction unassigned EBS was made in a July 2019 FCC rulemaking regarding EBS. But is auctioning the remaining EBS spectrum the right decision? Absolutely not. Here’s why:

First, the main reason the FCC created the TPW was because of a lack of broadband access on rural tribal lands. The same is true for non-tribal rural lands.

According to the FCC, 22.3% of Americans in rural areas lack coverage from fixed terrestrial 25/3 Mbps broadband. These communities have been overlooked by traditional broadband providers. Wireless technology changes the economics of traditional networks, making it more feasible to service rural lands. Why not give rural communities the same opportunity to access EBS as rural tribal nations?

Second, the TPW clearly demonstrates that rural communities are hungry for tools to help them deliver broadband, namely wireless spectrum.

At the time the FCC stopped issuing educational licenses in the 1990s, there were over 800 pending applications under review by staff. Sadly, the FCC’s series of decisions has meant that EBS covering approximately 50 percent of the U.S. geography has never been licensed by the Commission. Nearly 25 years later, demand is still high for this asset. In its paperwork to the Office of Management and Budget last year following the EBS rulemaking, the FCC severely underestimated the number of tribal nations that would apply for spectrum in the window. That wildly inaccurate estimate was easily surpassed, as over 400 applications were filed. More rural communities and educators deserve an opportunity to access this resource.

Third, a commercial auction will slow the deployment of broadband in rural communities.

According to the new EBS rules, the FCC is requiring Rural Tribal Nations that successfully acquire licenses through the TPW just 2 years to reach 50% population coverage, and 5 years to reach 80% population coverage for the license area. For licenses auctioned by the FCC, the benchmarks are extended. Auction winners – likely commercial operators – would have 4 years to reach 50% and 8 years to reach a final buildout of 80%. While the final benchmark is greater than for most other spectrum bands, for rural communities still waiting for broadband access, an 8-year wait is too long. A Rural Educator Window with a stringent buildout requirement will reach communities faster.

Fourth, there is already a significant amount of spectrum in the hands of commercial providers all across the country, including rural areas. Giving them more won’t necessarily solve the digital divide.

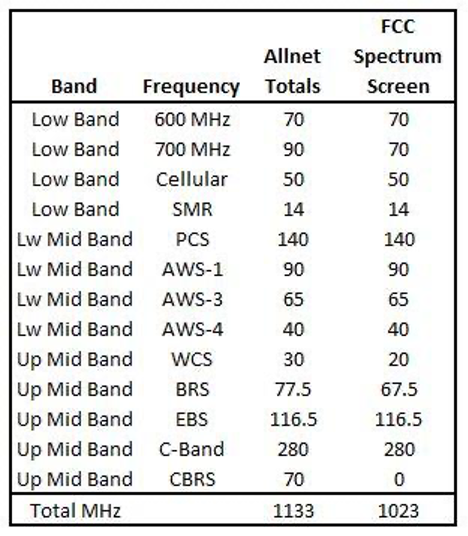

As Voqal pointed out in its comments to the FCC during last year’s EBS rulemaking, commercial carriers already control over 650 MHz of spectrum below the 6 GHz range, which is ideal for rural broadband buildout. Giving carriers more spectrum without adding buildout rules that are meaningful will not help close the digital divide.

Source: AllNet Insights & Analytics

Next, commercial carriers are set to get even more spectrum.

Just last week, the FCC concluded an auction of an additional 70 MHz of mid-band spectrum known as the Citizens Broadband Radio Service (CBRS) band. From our analysis of the results, just two universities – Texas A&M and University of Virginia Foundation – and one regional education service agency were successful in winning a total of nine licenses. With over 22,000 licenses available, that’s not exactly a high success rate. In addition to CBRS, the FCC plans to conduct an auction for a whopping 280 MHz of mid-band spectrum this December. In all, that means carriers will control over 1100 MHz of spectrum, not to mention their hundreds of MHz of high-band frequencies. Does the commercial sector really need all of EBS, too?

Finally, licensing EBS to educators does not mean commercial carriers are denied access.

There are some incredible examples of EBS deployments by rural communities and educators. But it is true that most EBS spectrum that has been licensed is leased to a commercial provider – either mobile or fixed. Issuing new licenses in a Rural Educator Window would give local communities an option to either deploy their own network or partner with a commercial carrier. That gives the local community control of how the license is used where they live. Having this lever will allow communities an opportunity to decide what is best for them. If commercial carriers can offer a good enough lease deal, I would predict many rural communities would gladly agree to lease their spectrum if it helped further their goal of connecting students and families in need. If the economics don’t support a lease arrangement, rural communities can pursue their own deployments.

The Rural Tribal Priority Window demonstrates just how eager rural communities are for tools to help close the digital divide. But the TPW also shows that auctioning EBS rather than offering it to local educators and communities will foolishly forego a critical opportunity to help other rural communities meet their connectivity needs.