The future of 5G has important ramifications for expanding high-speed internet access across the country and bridging the digital divide. In the following post, Voqal’s director of telecommunications strategy, Mark Colwell takes a deeper look at the future of this emerging technology.

Earlier this month, the Technology Policy Institute (TPI) hosted its 10th annual technology and telecommunications extravaganza known as the TPI Aspen Forum. This year’s event featured a who’s who of tech and telecom superstars, including Department of Justice (DOJ) Assistant Attorney General for Antitrust Makan Delrahim, Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Chairman Ajit Pai and dozens of other industry and policy experts.

During a Tuesday morning Q&A discussion between Chairman Pai and journalist Leah Nylen of MLex, former Executive Director of the National Broadband Plan, Blair Levin asked, “What is the metric for leadership in 5G? Is it price? Is it speed? Is it all kinds of other things?” Chairman Pai responded that “You’ll know it when you see it.”

If that is the case, what exactly do we see with regard to 5G today? I took a look at various articles and op-eds from the past few weeks to provide some insight.

Speed

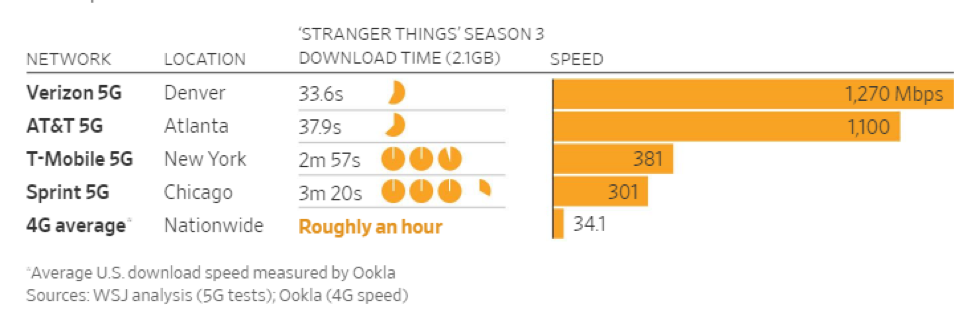

One of the obvious advantages of 5G, at least from the consumer perspective, is how much faster 5G networks will perform when compared to 4G networks. In July, the Wall Street Journal decided to test current 5G networks on America’s four largest carriers – Verizon, AT&T, T-Mobile and Sprint. Reporter Joanna Stern downloaded all 2.1 GB of the third season of Stranger Things on Netflix. The findings were “crazy fast,” but also “a hot mess” according to her analysis. The Verizon network edged out AT&T as the fastest network, allowing the reporter to download all 2.1 GB in just under 34 seconds.

One of the most critical findings is that 5G phones operating on higher frequencies (all carriers except Sprint) often overheat due to the high processing required. In order to preserve battery life and avoid overheating, the phones revert back to 4G speeds. In other words, July probably isn’t the best month to be testing 5G outdoors.

Coverage

Another key finding from the Wall Street Journal article was the lack of coverage. Before looking at 5G coverage today, it is important to take a look back at the deployment of 4G. U.S. wireless operators first launched 4G in the 2010 and 2011. Nearly a decade later, there is still work to be done to extend coverage to all Americans. According to the FCC’s 2019 Broadband Deployment Report*, 4G LTE coverage with median speeds of 10/3 Mbps is currently available to:

- 89% of all areas.

- 92.6% of urban areas.

- 69.3% of rural areas.

*Many contend that the coverage maps submitted to the FCC by wireless providers are wildly inaccurate. More on that in a future blog post.

Despite the ongoing urban-rural gap in 4G LTE coverage, 5G is here and carriers are now racing to deploy it in urban areas where it makes economic sense. According to AndroidPolice, 5G is available in the following areas:

- AT&T: 21 cities now, three more cities soon.

- Sprint: nine cities now.

- T-Mobile: six cities now.

- Verizon: 10 cities now, 15 more cities soon.

But while 5G is “available,” the signal only reaches a few pockets of these major cities. What’s worse, not all 5G is available indoors. As was noted by the Wall Street Journal’s Joanna Stern, Verizon had higher speeds but when she entered a nearby bakery, the signal dropped. That is because Verizon is using what is known as millimeter-wave spectrum to deliver its 5G signal. This spectrum is capable of carrying vast amounts of data but only for short distances. As one blogger observed, wireless users must be within 100 to 300 feet of the 5G node to get the best signal. In order for Verizon to extend 5G coverage on millimeter-wave spectrum, it will require much more infrastructure, resources and time to deploy. That, or somehow get lower frequency spectrum.

Sprint’s network, on the other hand, reached 301 Mbps but with a far greater coverage area. That is because Sprint is using 2.5 GHz spectrum, which provides greater coverage than millimeter-wave spectrum at 28 GHz. (Full disclosure: Voqal leases its 2.5 GHz Educational Broadband Service spectrum to Sprint.) While only nine cities currently have Sprint coverage, its 5G network is already available to 11 million people and covers 2,100 square miles. As other major carriers roll out their super-fast, albeit limited coverage 5G networks, Sprint, while slower, has a significant advantage in coverage. Voqal will follow this closely.

Price

While 5G speeds promise to be fast, costs promise to be high. Higher prices could come in two forms – higher device costs and higher monthly service bills.

When it comes to devices, the evidence already shows steep increases in cost. A new report from IHS Markit’s Josh Builta validates this analysis. According to the report, popular phones like the new Samsung Galaxy S10 5G phone, which was used to conduct the Wall Street Journal testing, could cost as much as $1,300. That’s a 335% increase over the 4G model, according to the IHS report. Unfortunately, prices well over $1,000 look to be the norm in the early days of 5G.

As with any new technology, prices tend to be the highest for early adopters and will drop when more handsets are available. The report also observes that in 2019, handset shipments will be just 9.5 million globally, growing to as much as 425 million by 2023. The majority of these 9.5 million handsets are offered in South Korea, where carriers predict two million customers by the year’s end. South Korea also just made available 28 GHz spectrum (the same as used by Verizon) and new 3.5 GHz licenses. The 3.5 GHz mid-band spectrum (similar to what Sprint currently uses for its 5G) is an important set of frequencies for carriers.

In addition to higher phone prices, it would not be surprising to see carriers add a 5G surcharge to bills. In March, Verizon announced a $10 add-on fee for 5G. It remains to be seen if other carriers will follow suit or if competition will keep prices in check.

What America Should Do

One reason America is trailing global competitors in the early days of 5G has to do with policy – specifically the availability of mid-band spectrum. Next generation 5G networks require a combination of three types of frequencies: low-, mid- and high-band. Today, all the major carriers control at least some low-band frequencies, which are best for extending coverage long distances but carry less data. Three out of four (Sprint being the only exception) have licenses for high-band spectrum, which is best for high capacity, but that has limitations in terms of how far the signal reaches. The goldilocks spectrum is mid-band, which is good for both coverage and capacity. Mid-band is the workhorse of 5G networks, yet only one major U.S. carrier has access to large, contiguous blocks of mid-band spectrum in major markets. That carrier is Sprint.

Sprint’s treasure trove of spectrum is one reason why T-Mobile has moved to acquire the company. If America really wants to win the race to 5G, it must make more mid-band spectrum available. Other options, including the 3.5 GHz and 3.7-4.2 GHz bands, are years away from deployment. 2.5 GHz is being used today, but only by a single U.S. carrier.

The FCC and DOJ missed an incredible opportunity to help create two powerful 5G networks by failing to require divestiture of 2.5 GHz spectrum as part of the T-Mobile/Sprint merger. Allowing New T-Mobile to control the only large chunk of mid-band spectrum is not only a problem for competitors hungry for mid-band, but also hurts consumers who will miss out on the benefits of strong 5G competition for years. While the DOJ and FCC have already approved the T-Mobile/Sprint merger, a pending lawsuit by 16 states is set to go to trial in early December. The result of this case could decide the fate of 5G in America for the foreseeable future.

Interested in learning more about this issue? Contact Mark at mcolwell@voqal.org.